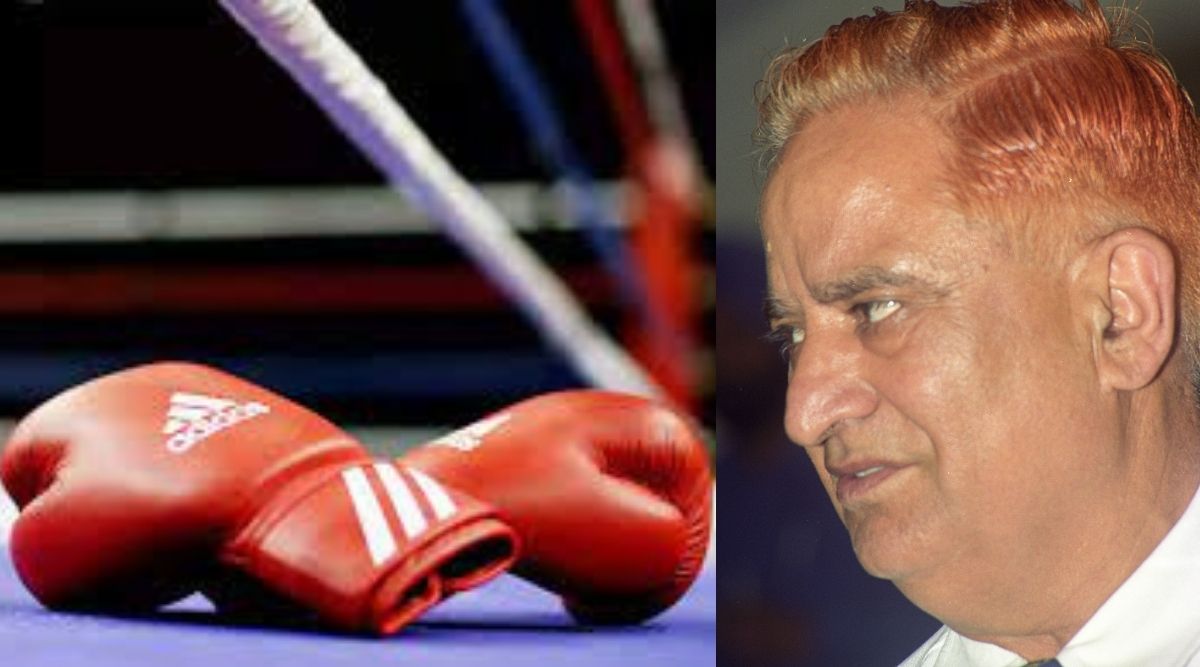

Om Prakash Bhardwaj, boxing’s first Dronacharya Awardee coach who passed away on Friday, did not have to step into the ring to pack a punch. A typewriter, instead, would do the job for him.

From a tour to Russia in the 1970s, Bhardwaj brought one with him to Patiala and using just one finger to type his letters, he routinely sparred with the federation over the facilities provided to the boxers. “Frequently, his letters used to land at the federation office and he wrote whenever he desired,” says former secretary of the erstwhile Indian Amateur Boxing Federation, Ashok Gangopadhyay. “His list of demands was long but it was always in the best interest of the boxers.”

The same boxers, whom he used to put through a ‘great amount of suffering’ in training. “He strapped weights to our bodies and made us run for miles… sometimes in the sand. Very rigorous physical training to make us stronger…” former India boxer-turned-coach Munuswamy Venu, who trained under Bhardwaj, recalls.

These two facets sum up Bhardwaj, considered a pioneer in Indian boxing. He passed away in New Delhi due to a prolonged illness and age-related issues, a little more than a week after losing wife Santosh. Bhardwaj was 82.

First signs of success

He was India’s boxing coach from 1968 to 1989, a period when India won dozens of international medals, especially at the Asian level. The period between 1970 and 1986 was particularly successful. Some of India’s finest yesteryear pugilists – including Birender Thapa, Kaur Singh, J L. Pradhan, Hawa Singh, Jaipal Singh and MK Rai – began their careers under Bhardwaj.

A havaldar with the Army Physical Training Corps (APTC), Bhardwaj was a boxer himself for a brief period before becoming one of the first coaches to obtain a boxing diploma from the National Institute of Sports in Patiala. Soon after, he took a plunge into coaching and remained in the role for the decades that followed, according to former IABF secretary-general Brigadier (Retd) PK Muralidharan Raja.

“Back then, the Services was a powerhouse in Indian boxing. There were 12 weight categories in international tournaments and all the spots were taken by Services boxers, who dominated the national championship and often won the titles without much trouble,” Raja says. “Even among the Services men, the boxers from Army took up a majority of the positions.”

It also helped, Raja adds, that one of the most influential persons in Indian boxing administration at the time, Devine Jones, was also from the APTC. Jones was the Indian boxing team’s coach at the 1972 Munich Games, was one of the few international referee-judges from the country, and went on to become the federation’s secretary-general from the mid-70s to early 80s. “So apart from his qualities as a coach, Bhardwaj also got support from the APTC and the federation,” Raja says.

Pragmatic approach

Venu says that in absence of much coaching literature in terms of tactics and technique, Bhardwaj’s primary focus remained on producing boxers who were physically very strong. “He was extremely hardworking and expected the same from us. His training regimen was very strict,” Venu says.

At times, Bhardwaj would himself run miles with his wards to push them even more. “He would always be involved in whatever the boxers did – be it running or sparring. He did not like to stand in the corner and shout out instructions,” says former India coach Gurbax Singh Sandhu, who was one of Bhardwaj’s students at the National Institute of Sports.

In 1985, when the sports ministry introduced the Dronacharya Award, Bhardwaj was feted along with Bhalchandra Bhaskar Bhagwat (wrestling) and O M Nambiar (athletics). “He ensured there was a steady stream of boxers in an era when things were not that easy. He laid the foundation for us to become one of the better teams in the world today,” Sandhu says.

The ripple effect of what Bhardwaj, who even taught some techniques to Congress MP Rahul Gandhi, did decades ago is felt even today. The boxers he trained went on to become trainers themselves. From Sandhu to Venu to Shiv Singh, Bhardwaj’s pupils are carrying his legacy forward.

Under Sandhu, India won its first Olympic medal when Vijender Singh claimed a bronze at Beijing 2008. “Although I never trained under him, I was aware of the impact Bhardwaj sir had on Indian boxing. I had heard stories of the kind of hard taskmaster he was and Sandhu sir, along with my other coaches who once trained under him, tried to implement a lot of his styles,” Vijender says. “I wonder if we would ever be in a position to win an Olympic medal without him. His hard work has inspired many generations.”