Written by Clifford Coonan

As the harsh realities of China’s growing power sink in, the county’s appeal is diminishing in the West. To keep it in check, more coordinated efforts are needed and come September the tone from Germany may be decisive.

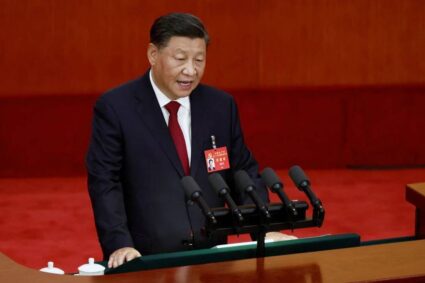

There are cracks appearing in the New Silk Road, otherwise known as the Belt and Road Initiative. Launched in 2015 as Chinese President Xi Jinping’s signature foreign policy project, it received a warm welcome from countries keen to benefit from Chinese globalization.

Since then, the attitude to China has hardened, especially in many democratic countries. Revelations about 1 million Uyghurs held in reeducation camps and reports of forced labor in Xinjiang, serious questions about China’s handling of the coronavirus and its origins, and Beijing’s dismantling of democracy in Hong Kong have cooled international enthusiasm for Xi’s pet project.

Western countries have been emboldened by a reset of relations under US President Joe Biden, following the chaos and division of the Donald Trump era. The Biden administration is pointing to growing Chinese aggression and looking to forge an alliance with Europe and its other traditional allies.

Leading the way on pushback is Australia, whose prime minister, Scott Morrison, said he did not think the New Silk Road was “consistent with Australia’s national interest.”

Relations between Canberra and its largest trading partner have nosedived since Morrison’s calls for Beijing to allow independent investigators into Wuhan to probe the origins of the coronavirus. Despite a free trade agreement and a slew of other free trade deals, China piled trade sanctions on Australian goods like coal, wine and barley.

For their part, Australia is reviewing whether to force Chinese firm Landbridge to sell a lease to the strategically important Port of Darwin, which is used by American marines, a move that could further stoke tensions with Beijing.

A similar tone is coming from neighboring New Zealand, where Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern spoke of how systemic issues with China were getting “harder to reconcile.”

Keeping China appeased

World leaders and CEOs alike are used to verbal dexterity — or simply being silent — when dealing with the authoritarian Communist Party leadership in Beijing.

Balancing the need to keep China appeased because of its economic might, while also staying true to values and democratic principles, has become a key geopolitical challenge. But rather than constantly bowing to Chinese demands, the European Union needs to realize the enormous strength it possesses in competitiveness and innovation.

China is the EU’s biggest trading partner, with a total volume of $686 billion (€570 billion) in 2020. In December, German Chancellor Angela Merkel led the EU to sign the EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment. For Merkel the CAI seems as important as the Silk Road project is to Xi Jinping.

It was probably the high point of EU-China relations. In the meantime, fresh revelations about Xinjiang and an intensified crackdown in Hong Kong have seen relations deteriorate.

The EU has since imposed coordinated sanctions against four Chinese officials over internment camps for Uyghurs. Beijing responded quickly, targeting 10 individuals including German researcher Adrian Zenz, who played a key role in bringing attention to the Xinjiang camps.

Europe taking steps against takeovers

On top of all that, the COVID-19 pandemic has devastated economies and depressed the equity valuations of European companies, leaving firms vulnerable to takeover bids from China.

EU giants like France, Italy and indeed Germany were finally spurred into action. They beefed up their powers to block acquisitions of prized European assets from outside the bloc.

In 2019, Italy caused consternation when it became the first G7 country to enthusiastically back the Belt and Road Initiative. Since then, Mario Draghi’s government has changed tack, blocking planned Chinese acquisitions of Italian firms, most recently the sale of Turin-based Iveco’s truck and bus unit to China’s FAW.

Despite this pushback, many experts think that efforts need to be better coordinated. The EU especially needs to be more strategic about Chinese projects in its own backyard.

Angela Merkel’s approach has been to repeat familiar calls for dialogue on human rights. The accepted wisdom has long been that German industry is operating in a values-free zone, focused exclusively on the bottom line and repeating the mantra: change through trade.

But German firms are aware of the changing political and economic realities in China. Hopes that China would become more liberal and a better global partner have failed to materialize.

What will the Greens do?

The biggest shift could be yet to come, once Merkel steps down. Polls in Germany show the Greens are on course for a significant role in government after September’s election. Their chancellor candidate, Annalena Baerbock, has taken a hard line and accused Merkel of taking a passive approach to China.

Human rights have a role to play in the European relationship with China. Bowing to pressure from the Communist Party will have disastrous long-term effects on European companies. Yet how can European companies compete with Chinese ones if they are using forced labor in their cotton factories and building cars with enormous state subsidies, using technology transferred from Western brand leaders?

European companies need to remember how to play by their rules, which are also global norms. Sluggish reforms and a lack of level playing fields pose a serious threat to the ability to do business in China. The country needs to reform and become a better global actor if it truly wants to compete, no matter how vast and alluring the market may be.